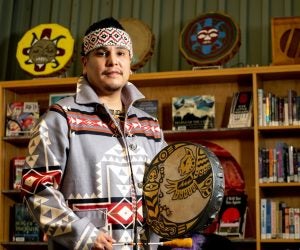

Through cultural learning, CUPE 389 member Dallas Guss is making a difference in K-12

NORTH VANCOUVER—When CUPE 389 member Dallas Guss reports for work at School District 44, he’s bringing with him cultural teachings that are thousands of years old.

NORTH VANCOUVER—When CUPE 389 member Dallas Guss reports for work at School District 44, he’s bringing with him cultural teachings that are thousands of years old.

Guss, a member of the Squamish Nation, works as an educational assistant, Indigenous support worker, and cultural support worker in various North Vancouver schools. For the past three years he has also provided cultural teaching in a district that’s committed to Indigenizing schools—reversing the effects of the colonial teaching model by including the Indigenous perspective.

Of all this work, perhaps his most rewarding role is providing Indigenous support. Guss not only helps Indigenous students learn about boundaries in the classroom—those rules of interaction that are not necessarily part of Indigenous culture—but also to understand that there are specific times to do specific things. He also enjoys helping teachers understand how to approach a student with an Indigenous background.

“This role has been really successful in helping teachers understand the Indigenous perspective, so that there can be less conflict, issues, or problems,” says Guss. As for the students? When he sees children having a problem, he prefers not to jump in to solve it for them but instead give them a chance to work it out for themselves.

“I encourage them to have their own space and build their own problem-solving skills,” he says.

Repairing a broken relationship

School District 44 began the journey to Reconciliation in 2016 when three North Vancouver schools were among the first five in Canada to sign on to the Legacy Schools program, a free national initiative “to engage, empower and connect students and educators to further reconciliation through awareness, education and action.” The program was inspired by Tragically Hip singer Gord Downie’s The Secret Path, which told—first in poems and then in an album, a graphic novel, and an animated film—the tragic story of Chanie Wenjack, a 12-year-old Ojibwe First Nations boy who in 1966 ran away from the residential school where he’d been boarding for three years, dying of hunger and exposure while trying to walk home.

As a member of school district staff, Guss appreciates the Legacy Schools program because it’s important for today’s students to understand the lasting impact of residential schools on Indigenous communities.

“It’s not just facts in a history book,” he says. “I’m talking about my parents, my aunties and uncles, my grandparents and so on. It is really deeply personal.”

Teaching about current events, Guss helps students understand how Canada’s broken relationship with Indigenous people still needs lots of repairing. But he also lets them know how recent acts of resistance are literally changing the world: citing the Wet’suwet’en pipeline conflict and more recently the Mi’kmaq fishing dispute, he tells students that if these events had happened even three-to-five years ago, Canadians would not have given the same support as they have in the past year. “By understanding and sharing what they learn at home and in their community, District students are getting Indigenous culture into Canadians’ conversations,” says Guss. “It’s literally changing our world for the better.”

Changing how we educate

The Indigenous perspective is not based on a top-down model of leadership but instead is cooperative—it’s about doing what’s best for the people. Dallas grew up under the influence of that model thanks to his mother’s father, who was the first Band manager, and his father’s mother, a Councillor and Chief in the Squamish Nation. He still hears stories about what a great leader his grandfather was. He would visit every home and talk with everyone before reaching consensus based on those discussions.

“I am really grateful that I came from such loving leaders. My ancestors welcomed outsiders with open arms and did their best to give all the teachings to everybody who came in,” says Guss, adding that his ancestors accepted everyone as a human being regardless of skin colour, background or religion.

In his work, Guss has taken District 44 staff and students up into the mountains, into a longhouse, and to traditional sites. He has done tours in Vancouver’s Stanley Park and, in the park’s east end, shown participants where a Squamish village had been. When he shares cultural teaching, he models his ancestors: the best communication is open, understanding and accepting, with no separation, division, or withholding. He also validates and acknowledges non-Indigenous people in the District who are interested but feel uncomfortable sharing Indigenous teachings. The Indigenous team motto for the last three years, he says, has been to “go forward with courage.”

Active on Twitter, Guss enjoys a good debate and dismisses attempts to pigeonhole him as “liberal” or “far left.” Indigenous people, he says, don’t recognize such ideological concepts, which are rooted in European political thought and a system of government that was brought here: “We come from a system of highly advanced spiritual leaders who spent a lifetime gaining tools not only to represent their people, but to represent everything on earth — water, the air, the trees, the animals, sea life, and everything in between.”

At the beginning of the pandemic, the District asked Guss to submit some Indigenous stories for the curriculum that might help students cope during difficult times. He chose specific Squamish legends that tied into what people are experiencing through COVID-19. Taking a group of Grade 3 students to the Big House in Squamish, he shared the legend of Wountie, whose message is not to take more than you need. Sharing the legend in schools, he showed students pictures of grocery stores with empty shelves and explained that nothing was saved for elders and the most vulnerable members of our community. Students, recalling what they’d learned about Wountie, instantly made the connection: a legend thousands of years old was still relevant today.

Almost half of CUPE members in the K-12 sector are student support staff. These workers are integral to student development and public education, assisting teachers and delivering education programs to students.